Audio Stories

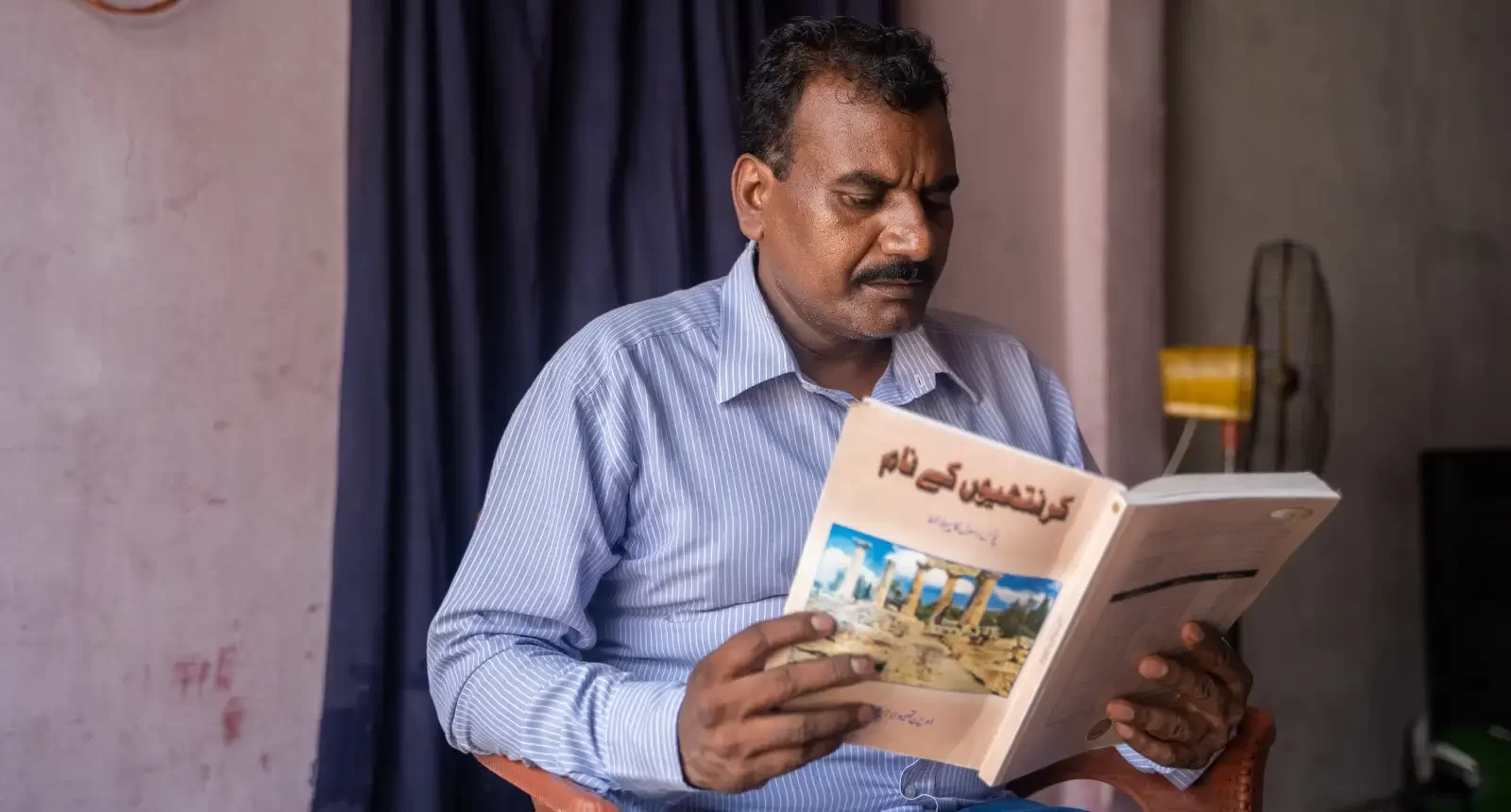

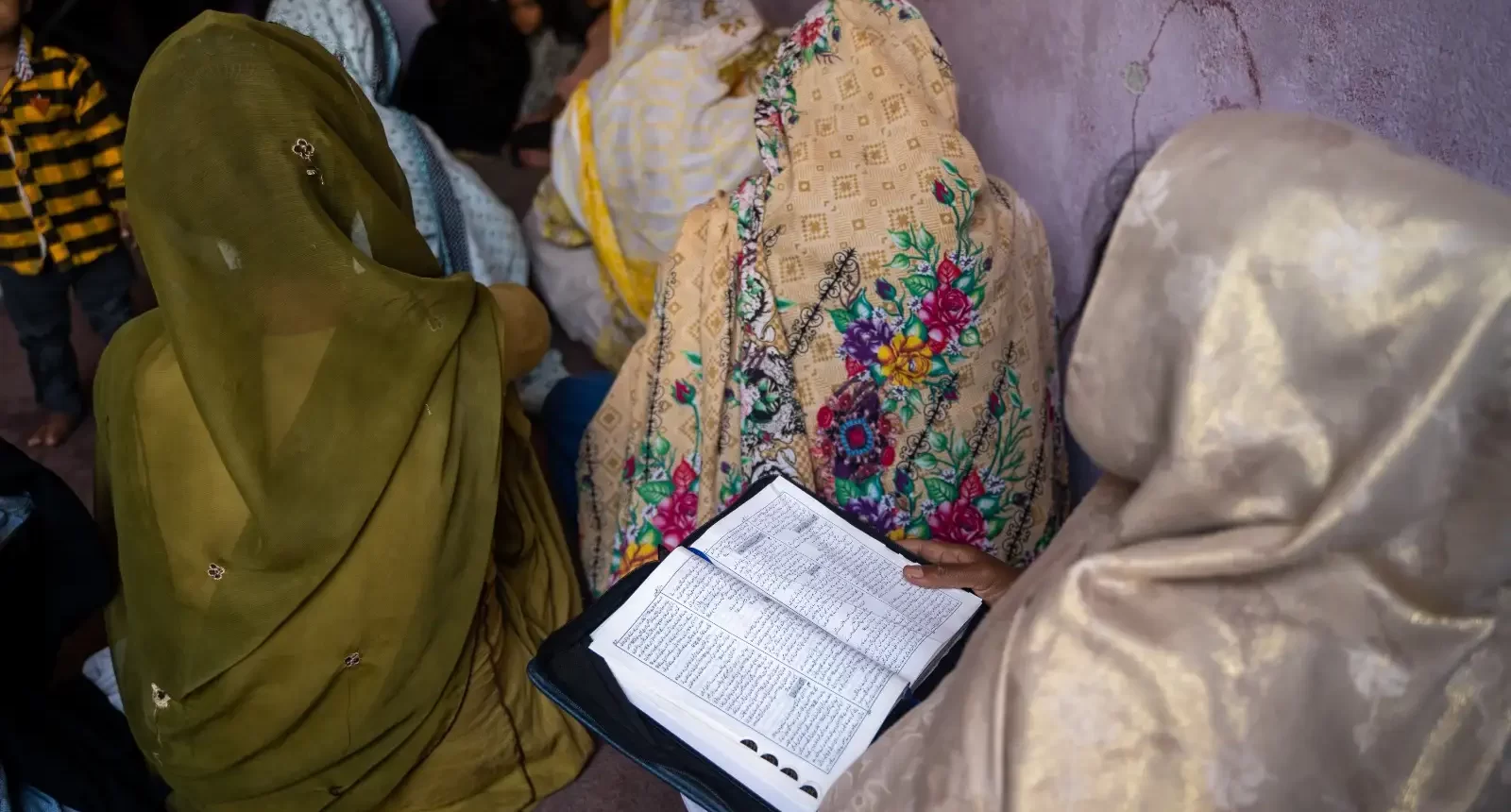

Shahzad Masih

Riaz Masih

Fauzia

Bilqis

Photo Stories

Rimsha Colony is a Christian slum settlement situated in main Islamabad, specifically in Sector H-9/2, accessible via a service road near Kirthar Road. This settlement comprises 1,400 housing units and houses an estimated 2,700 to 3,000 families, with a population ranging from 14,000 to 16,000 individuals. Many of the residents of this settlement were displaced from Mehrabadi, G-12 sector in Islamabad, due to a blasphemy case involving Rimsha Masih, a minor girl with Down syndrome, in August 2012. Rimsha was arrested on August 16, 2012, and was subsequently cleared of charges on November 20, 2012, after securing bail for $10,500 (£6,200). The case generated strong reactions from the Muslim community, resulting in threats against Rimsha and her family. In June 2013, they were forced to relocate to Canada due to ongoing threats. It is important to note that the case against Rimsha was later proven to be false, with the individual responsible, Khalid Chishti, a Muslim cleric, admitting to planting pages of the Quran among burnt pages in the girl's bag.

In response to death threats and the hostile environment in Mehrabadi, hundreds of Christian families swiftly relocated to save their lives, leaving behind homes that were subsequently burned and looted. The Capital Development Authority (CDA) allocated a plot of land in Islamabad's H-9/2 area to provide these families with a place to rebuild their lives, which became Rimsha Colony. Initially, the land was undeveloped, and residents had to clear the bushes and construct huts, which have since been converted into houses. While they were promised food and shelter by the government, these assurances were never fulfilled, leaving their future uncertain.

The community residing in Rimsha Colony faces a myriad of challenges, including workplace discrimination and frequent encounters with Pakistan's blasphemy laws, which are sometimes misused to settle minor disputes. The Rimsha Masih case serves as a notable example, causing deep trauma and anguish within the Christian community when such incidents occur.

Access to necessities, such as electricity, sewage systems, and clean water, poses a significant challenge for residents. The settlement remains unconnected to the electric and sewage grids, compelling residents to either purchase drinking water or fetch it from distant sources. This lack of access to clean water has resulted in health problems, particularly among children and pregnant women. To compensate for these services, many residents rely on solar panels for electricity, use LPG for cooking and heating, and hire private contractors for waste disposal.

In terms of employment, a substantial portion of the settlement's male population works as sanitation workers, primarily for the CDA, while the majority of women are employed as domestic workers in nearby sectors. The absence of government schools and basic health facilities in the settlement has led to an increased school dropout rate, especially among girls, who often find themselves working as underage maids. Unfortunately, these girls are vulnerable to various forms of violence and abuse, including the threat of abduction.

An ongoing challenge faced by the community is the threat of eviction and displacement, as they regularly encounter harassment from the CDA. Despite a Supreme Court injunction temporarily preventing eviction, the CDA has sealed three tube wells in the area in an apparent effort to compel residents to leave. Furthermore, the construction of the 10th Avenue on a service road poses a potential risk of displacing up to 1,400 households within the settlement. Despite these formidable challenges, the residents of Rimsha Colony exhibit resilience and continue to advocate for their rights and place within Pakistani society.