The anthology we compiled as the Climate and Conflict’ Displacement Stories’ from Karachi and Islamabad at TheDisplacement.com is a compelling exploration aimed at humanizing the profound impact of displacement caused by climate-induced and conflict-driven events. Within its pages, this anthology delves into the intricate facets of displacement, dissecting the elements of climate and conflict that uproot communities across Pakistan.

Under the spectrum of climate displacement, the anthology meticulously scrutinizes the repercussions of floods, droughts, landslides, and GLOF (Glacial Lake Outburst Flood) events. We compiled trends of displaced communities in the South and the North by focusing on Karachi and Islamabad. Simultaneously, this platform sheds light on conflict displacement, encompassing intercity, internal, and cross-border displacements, each event amplifying the long-standing uncertainties entrenched within these communities.

A focal point of this anthology is the examination of displacement patterns and their enduring impact on the well-being of affected communities. Beyond the immediate upheaval, the anthology contemplates the rippling effects, often fostering ethnic and racial tensions that exacerbate the plight of both displaced and host communities.

Each displacement event, whether induced by climate or conflict, leaves an indelible mark, fostering an enduring sense of insecurity among these communities. The anthology poignantly articulates the profound and enduring struggle for stability in the wake of such upheaval.

To address these multifaceted challenges and pave the path toward resolution, this anthology emphasizes the urgent necessity for comprehensive, actionable policy initiatives. These policies aim not only to mitigate the immediate impacts but also to foster resilience and create sustainable solutions for the marginalized and displaced populations in Pakistan.

In essence, TheDisplacement.com serves as a clarion call for proactive policy interventions, advocating for a future where the right to security and stability is upheld for all communities affected by displacement.

Displacement, Migration, and Refuge

As a proletarian understanding, displacement is simply defined as “the act of forcing somebody/something away from their home or position” (Oxford Learners Dictionary, 2023). Shamsuddoha et al. (2011) explain that displacement is a form of migration where people are forced to move against their will. The concept of displacement differentiates from migration and asylum-seeking based on a few conditions. This is because asylum seekers leave the country after fleeing from the country due to a reason. On the other hand, migration can occur (internally or internationally) after an individual either willingly or is forcibly forced to move to another location. Displacement and asylum are significantly similar under the conditions that force people (Shamsuddoha et al., 2011). However, displacement is more uncertain than migration and asylum, which offer a kind of certainty.

Displacement has several kinds, i.e., one where people are forced away from their homes either at the hands of a condition or other people. Displacement occurs in various forms. Developmental displacement occurs when people are forced to move due to large-scale development projects like dams, highways, or urban redevelopment. On the other hand, economic displacement happens when individuals or communities move due to economic reasons such as the loss of jobs, declining industries, or lack of economic opportunities in their home region (Terminski, 2014).

Climate displacement is the migration process because of climate change factors and disasters. It draws attention to the gaps and inequities in less developed nations. The threat to food security, health, and economic stability due to climate change complicates social and ecological issues there (Mapping Displacement, 2022). Conflict displacement refers to the movement of people forced to leave their homes or places of habitual residence due to armed conflict, generalized violence, or human rights violations. This type of displacement can occur within a country’s borders, leading to internally displaced persons (IDPs) or across international borders, resulting in cross-border displacement.

Conflict displacement is divided into internal, intra-urban, and cross-border (Alkhateeb, 2023). Intra-urban displacement is a specific type of relocation throughout the city, especially because violence or unrest has occurred in certain areas. People relocate to less perilous neighborhoods of the same city, dealing with housing shortages and unemployment. Internal displacement refers to relocation within the country. Unsafe areas of residence result in the movement away from homes into their country with safety (Alkhateeb, 2023). This results in resource strains for host communities and a restriction on access to support services. However, cross-border displacements involve the movement of people from their countries to seek safety beyond international borders. They eventually become refugees or simply asylum seekers in other countries where they must deal with the legal and cultural aspects that are related to the chances of building a new life again (Sepka, 2017). The different types of displacement pose specific challenges and necessitate targeted solutions that ensure the safety and rehabilitation of internally displaced people.

In its entirety and parts, displacement has been condemned by human rights organizations. Consequently, regulatory and governing bodies have set forth a range of conventions and standards for national and international displacement. The main international treaty is the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, which outlines refugee rights and protections (United Nations High Commission for Refugees, 2011). These documents state the states’ responsibilities towards people who leave their countries because of fear of persecution concerning race, religion, nationality, belonging to certain social groups, or holding political opinions. Second, the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement define a structure for IDPs’ rights and protection from displacement due to conflict, natural disasters, or human-related causes in their country (Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, 2023). These principles would guide the governments in enacting relief, protecting, and stemming dignity through solutions for IDPs.

Impact of Displacement on Communities: A Review of Pakistan

The communities that are displaced become more marginalized than even refugees and migrants because of various reasons. Displaced persons do not receive legal recognition or protection. In contrast to refugees whose status is recognized under international law and who can receive protection and aid, displaced persons might not enjoy such provisions. This lack of legal framework can restrict their access to fundamental services such as health care, education, and job opportunities (IOM UN Migration, 2023). Second, the displaced may not have prepared for the move and often leave hurriedly because of unexpected conflicts or catastrophic events. This sudden exit implies they would be short of funds, documents, and connections because refugees or immigrants could have time to plan before exiting the country.

The displaced communities might be forced to spend time in temporary shelters or camps that lack accommodations and security. In Pakistan, over 7.9 million people are temporarily displaced, and around 589,000 live in camps (IOM UN Migration, 2023). These people often struggle to fit into the local community, resulting in social isolation and financial problems. A review of Pakistan informs that the country is home to the largest displaced populations in the world and internally and internationally displaced people in acute need of healthcare, financial funds, shelter, and safety (IOM UN Migration, 2023). On the contrary, migrants choose their residence destinations freely and with a purpose or goal in mind – better occupation conditions desire to meet relatives. This organized migration enables them to better prepare for their new environment. Considering all that, the lack of a legal position and unorganized migration, together with scarce access to resources, make displaced communities even more marginalized compared to refugees and migrants (Khan & Sepulveda, 2022).

The population of displaced communities in Karachi and Islamabad has diverse challenges like violence and segregation, among others. In Karachi, such settlements are informal, and residents face forcible evictions and demolitions due to development activities. These populations are even more susceptible due to the lack of legal status and protection (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2020). There is a double displacement where they are resettled but have to be displaced once again, as witnessed after the reconstruction of Preedy Street and differentiation in 2017. Consequently, a report informs that only in 2014, around 67,000 Afghanis were living in Karachi, a number that has increased manifold since then (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2020). In Islamabad, this situation is also equally bad. For instance, approximately 1400 Christian families residing in Sector H-9 after the Rimsha Masih blasphemy case are going to be demolished to build a new highway. Deprived of tenure security, these families run the risk without legal protection or resettlement provisions.

The legal system of Pakistan, and especially the Land Acquisition Act of 1894, is inadequate protection for non-titleholders’ rights, resulting in many displaced families being left without compensation or support (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2020). Even though amendments were made in neighboring countries like India and Sri Lanka about providing fair compensation or resettlement plans, the policies of Pakistan still fail to meet the needs of displaced communities. Both Karachi and Islamabad, after that, turned out to be a cruel reality for the displaced communities who have taken refuge. However, they suffer the shock of losing their homes and are stuck with long-term issues relating to marginalization and areas with no legal jurisdiction (The Displacement, 2022a). The two cities have been forced to relocate due to displacement resulting from climate-related events such as floods, heat waves, and drought, as well as conflict-related issues caused by political and social unrest. Climate displacement has created places like Sindhabaad in Karachi, home to various people who moved from their settlements due to floods and drought (The Displacement, 2022b). These groups, from diverse backgrounds with troubles in their villages, have only found a temporary shelter that offers challenges such as poor sanitary conditions, limited availability of resources, and financial instability. They operate in the informal economy, make low wages, and have political, religious, and ethnic problems. The situation in Sindhabaad also illustrates the socio-economic complications surrounding climate displacement and their influence on settlement systems across Karachi (The Displacement, 2022b).

The mountain communities in Islamabad are bound to their ancestral lands and suffer greatly from climate displacement. They find themselves forced into this situation because of the need for an emergency shelter usually provided in urban centres such as Islamabad (The Displacement, 2022c). This migration puts the family’s strength to limits and, in this way, pulls out the socio-economic products of relocation. Although the communities have some resilience through their communal bonds, it is understood that climate events occurring with high frequency and intensity are driving them towards a displacement crisis (The Displacement, 2022a). These problems highlight the importance of preventative actions and government involvement in limiting these effects to support such communities.

Millions across Pakistan have been affected by climate and conflict-related displacements. The 2022 monsoon season, with unprecedented rainfall, unsettled the nation and displaced close to eight million people. In 2015, this was the worst displacement disaster of the last decade in regions like Sindh and Balochistan (Othering and Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley, 2022). Displaced persons had difficulty finding shelter, health care, and basic services. However, the majority sought refuge in shelters, which brought into focus the state of disaster preparation and response. In 2022 alone, around 8 million displaced people were within the country (Othering and Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley, 2022). Since around 1/3rd of the country was affected by the floods, most of the people travelled to urban regions within the country. The joint action of climate events and conflict has displaced people in different provinces. People in the province of Balochistan have been displaced both by counter-insurgency operations and nationalist violence, creating significant humanitarian needs (Othering and Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley, 2022). With no centralized reporting and the politicization of media coverage, it is impossible to get an accurate measure of the magnitude of conflict displacement.

Pakistani displaced populations, including Afghan refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs), have numerous challenges to address. Such issues include limited access to education, lack of proper healthcare and job opportunities, and legal integration problems. This precarious legal standing and lack of government support further complicate displaced communities’ challenges (Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, 2022). The case of the Bugti people in Balochistan, those forcibly displaced by counter-insurgency operations, sheds light on IDPs. Most of them live in extreme need without foreign support, highlighting the importance of developing special policies to help displaced people.

In conclusion, the significance of climate and conflict displacement in Pakistan goes beyond individual lives as it changes society’s economic fabric. It requires coordinated actions by the state, intergovernmental agencies, and civil society to address this challenge and adequately support the rights of displaced people in terms of long-term rehabilitation and resettlement. While the relationship between climate and conflict displacement may differ greatly across time, such variation depends on some factors, including environmental status and geopolitical situation.

Displacement Causes Food Insecurity:

Climate and conflict displacement significantly contribute to long-term food insecurity through various interconnected mechanisms that disrupt food systems, compromise livelihoods, and hinder access to sufficient and nutritious food over extended periods.

To understand this connection, let us analyze it deeper: displacement often leads to the loss or abandonment of farmland and livelihoods. Displaced populations are forced to leave behind their agricultural lands, livestock, and farming tools due to the impact of climate-related disasters or conflict. This separation from their primary sources of sustenance results in a long-term reduction in food production capacity, leading to continued dependence on external aid and limited opportunities for self-sufficiency, as well as reduced food production for other communities. Besides, the prolonged nature of displacement exacerbates food insecurity. Displaced individuals often endure extended periods living in temporary shelters, refugee camps, or unfamiliar environments. This protracted displacement strains available resources, disrupts traditional food systems, and limits access to income-generating activities, perpetuating their reliance on external assistance for sustenance.

Additionally, the psychological and economic toll of displacement contributes to long-term food insecurity. Displaced populations experience increased stress, trauma, and limited access to economic opportunities. These factors hinder their ability to rebuild their lives, including their capacity to engage in sustainable livelihood activities, thus perpetuating food insecurity even after resettlement or return to their places of origin.

Moreover, the impact of displacement reverberates within host communities and regions, leading to increased competition for limited resources, including food. This dynamic often results in tensions, strained resources, and an increased burden on local food systems, further amplifying long-term food insecurity for both displaced populations and their hosts.

Furthermore, climate change exacerbates these challenges by creating long-term environmental degradation, altering weather patterns, and increasing the frequency and intensity of natural disasters. These factors contribute to sustained disruptions in agricultural productivity, affecting food availability and accessibility not just for displaced populations but also for the broader communities affected by these changes.

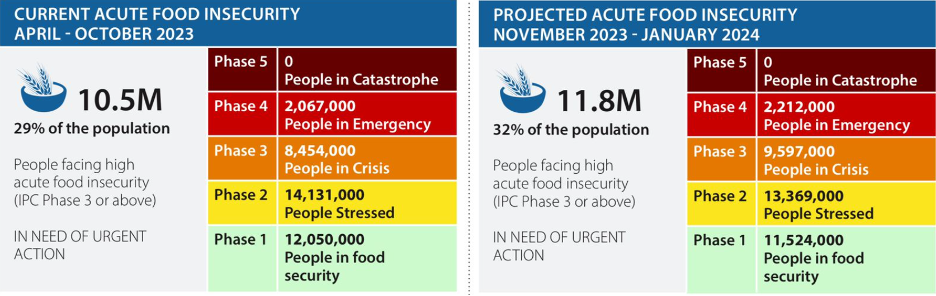

These effects have been observed in Pakistan as well; the [Integrated Food Security Phase Classification] IPC Acute Food Insecurity Analysis conducted in Pakistan in 2023 discusses these impacts in detail. The report covered 43 flood-affected rural districts in Balochistan, Sindh, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, encompassing 36.7 million people or 16% of the population, and identified that from April to October 2023, approximately 10.5 million people (29%) faced severe food insecurity, with 2.1 million in IPC Phase 4 (Emergency) and 8.5 million in Phase 3 (Crisis). The period coincided with the Rabi post-harvest season, Kharif season crops, and the monsoon period, requiring urgent actions to support livelihoods and reduce food consumption gaps. Most districts (38 out of 43) were in Phase 3, with 5 in Phase 2. Over 20 districts had 35-45% of their populations in Phase 3 or 4. The projection for November 2023 to January 2024 indicated a deterioration, with the number of people in Phases 3 and 4 expected to rise to 11.8 million (32%), a 12% increase compared to the previous period (IPC Acute Food Insecurity Analysis 2023).

The worsening food insecurity was driven by multiple shocks, including the severe 2022 monsoon floods, high food and agricultural input prices, poor political and economic conditions, livestock diseases, and adverse weather affecting Rabi season crops, notably wheat. These factors resulted in poor food security outcomes and were expected to continue affecting food access due to decreased household wheat stocks, reduced employment opportunities, high prices, and further climatic and crop challenges. The aftermath of the 2022 floods continued to impact food prices and livelihood opportunities, preventing the affected populations from achieving food security (IPC Acute Food Insecurity Analysis, 2023).

Figure 1: Current and Projected Acute Food Insecurity Analysis (Source: IPC Acute Food Insecurity Analysis, 2023).

In short, climate and conflict displacement perpetuate long-term food insecurity by disrupting food systems, livelihoods, and access to resources, creating enduring vulnerabilities that hinder the ability of affected populations to achieve sustained food security and self-reliance. Addressing these complex challenges requires comprehensive and sustained interventions that prioritize the restoration of livelihoods, access to arable land, and the development of resilient food systems for both displaced populations and their host communities.

In the methodological process of displacement research in Karachi and Islamabad, a general approach was adopted by utilizing existing literature and ethnographic mapping. This anthology, which is titled TheDisplacement.com, was built with the understanding of the necessity to use accessible data and literature as a base for elaborating it further instead of building everything from scratch. The foundation for this decision was the recognition that a large amount of already relevant information had been gathered and that the efforts of this research would be better utilized to complement, deepen, and expand such a knowledge base.

One distinctive element of the methodology was emphasizing Karachi and Islamabad, two cities selected for reasons explained on the About Us page of the repository, TheDisplacement.com. It was a pilot study aimed to map the patterns of displacement in cities that have somewhat a similar trajectory of expansion and are known to be established by the migrants rather than by any host community. Our approach allowed for an in-depth study of displacement within such urban settings to reveal this phenomenon’s complexities and social costs. This research sought to identify and understand these challenges and existing gaps as they were critical in shaping the general direction of this study.

The study identified two primary forms of displacement, including climate and conflict. In conflict, we delved into the subcategories to define the theoretical frameworks of conflict-induced displacement. The study of climate displacement was an important ethnographic piece to understand the nexus of climate and conflict and the gaps in rehabilitation. Nevertheless, the scope was restricted to delineating categories of data closely associated with the narrative mapping of these two forms of displacement. This tightening of the scope was necessary to ensure the findings remained clear and pertinent.

Ethnographic mapping was an essential part of the methodology used in conducting research. Using this method, ten distinct communities under the ambit of climate and conflict displacement were observed and recorded in great detail to provide a more complex description of the displacement picture for Karachi and Islamabad. A cluster study approach, particularly in mapping the Quetta Hazara Community, was an important strategy for capturing intricate processes along these communities. Moreover, the study also identified the climate displacement patterns in the North of Pakistan, including the mountainous region, and put it into perspective with the climate displacement in the South of Pakistan, which has plains as its topography.

The research data were compiled using the narrative mapping technique by extensively profiling 10 communities and putting them on the GIS Map. The narrative was further compiled and presented in the form of audio stories from each community. As a result, 28 audio stories were posted, along with more than 135 photo stories. These knowledge products played an important role in presenting the theoretical framework to the otherwise obscure landscape of displaced communities, often conspiring with migration or refugees.

Research Gap:

Among the major gaps identified during the research was that there were no national or international laws on displacement. However, this lack of legal frameworks is a major challenge in addressing and managing displacement efficiently. Finally, the approach to research methodology was diverse and multidimensional, incorporating a literature review and homogenous ethnographic mapping with various data collection approaches, including building a digital archive featuring policy briefs, research papers, news sources, and reports from the last 15 years. Further to this, TheDispalcement.com also has a Research and Analysis section that aims to keep updating and presenting the theoretical frameworks of displacement. Because of all these efforts, we were able to present this impactful policy brief, which needs immediate action through coordinated efforts. It also demands a pre-emptive approach to avert social insecurity, including health, education, housing, and food insecurity.

Ethical Consideration and Limitation:

In our study, participatory risk and vulnerability mapping serves as a key tool. This process not only generates valuable maps but also facilitates deeper community engagement, allowing for the collection of local knowledge and insights. This dual approach opens up new understandings of how host communities engage with displaced communities and vice versa. The data was collected only after obtaining consent from the respondents to reveal their identities. The consent form (See appendix) was read to them in Urdu and English both. Once they understood and agreed upon the form, the respondents were asked to sign it. After they had signed a consent form in English and/or Urdu, they were interviewed, and their stories were published. The author has the raw data, which is encrypted and will be discarded after six months. The researcher understands the sensitivity of privacy; therefore, the audio transcripts and identities of the respondents who did not agree to reveal their identities will remain hidden. The data and the respondents’ identities will not be shared with anyone under any circumstances.

While recognizing some limitations due to social and physical contexts, we gathered that the participatory mapping process itself offers significant benefits beyond the physical maps produced. Our research methodology also helped unpack the layered challenges faced by climate and conflict-displaced communities and the parallel vulnerabilities experienced by host populations.

Over the past two decades, Pakistan has witnessed significant moments in its history marked by a substantial level of intra-urban, internal, and cross-border displacement. Notable occurrences contributing to this phenomenon include the devastating 2010 Superfloods, military operations conducted in the country’s northwest during the 2000s and 2010s, and, more recently, the 2022 floods. These events have compelled communities in Pakistan to contend with the challenge of forced displacement, resulting in profound implications for the socio-economic landscape of the country.

In spite of the constitution’s commitment to safeguarding the dignity of all individuals, those who have been displaced often discover a lack of adequate safeguards. This underscores the necessity for specialised mechanisms and legal frameworks for protection that guarantee the upholding of their rights in the aftermath of traumatic events. Beyond immediate protection, there arises a pressing need for comprehensive measures to facilitate the eventual rehabilitation and resettlement of these communities, recognising the enduring impact of their experiences.

The institutional framework for addressing the displacement landscape in Pakistan involves various government agencies, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and international partners. The following are some of the institutions and mechanisms that can upgrade their institutional capacity and build their strength in order to address the plight of Pakistan’s displaced communities.

National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA)

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) is a governmental organisation responsible for coordinating disaster response management efforts within Pakistan. It was also solely responsible for the rehabilitation of the communities displaced from the northwestern part of the country because of military operations. The NDMA operates as the executive arm of the National Disaster Management Commission (NDMC), which was established under the chairmanship of the prime minister as the apex policy-making body with regard to disaster management. The NDMA has a crucial role designated to it in addressing various types of disasters, including those caused by natural events like floods, earthquakes, and climate-related challenges, as well as by IDPs of conflict. In the face of a national-scale disaster, the NDMA has the task of assuming a pivotal role by acting as a central coordinating body. This responsibility extends to engaging with a diverse array of stakeholders, including various government ministries, departments, the armed forces, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), and United Nations (UN) agencies. The NDMA’s mandate encompasses the intricate task of fostering collaboration among these entities to ensure a unified and effective response to the crisis at hand. When it comes to internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Pakistan, the NDMA is mandated to coordinate efforts to provide relief and support to those displaced due to a combination of climate-related factors as well as conflicts. Under the National Disaster Management Act of 2010, the NDMA, the Provincial Disaster Management Authorities (PDMAs), and the District Disaster Management Authorities (DDMAs) have the task of assessing, planning, responding, and rehabilitating, with the efforts being coordinated across the board. Hence, the response is effective and proportionate. These bodies also have the task of initiating activities around recovery when the emergency has ended and, in some cases, undertaking those efforts alongside relief, with the focus being on shelter, food security, agriculture, health and nutrition, education, and livelihood.

The central issue in mitigating the risks associated with disasters revolves around financial resources. In this respect, the federal funds are to be overseen by the NDMA. At the provincial level, substantial funds are annually allocated to provincial disaster management authorities (PDMAs) by their respective provincial governments. For example, for 2023-2024, the Sindh government has earmarked PKR 1,962.451 million for rehabilitation, a portion of which is specifically for the province’s disaster management authority. However, while budgets are allocated for these purposes, it remains unclear how successfully governments have been able to carry out the process of recovery and help communities resettle in their original dwellings since there are communities that were affected by natural or especially climatic disasters and are still displaced. Sindhabad settlement on the M-9 motorway and 500 Quarters, Musharraf Colony, located at Hawkesbay Road, are two of the many such examples. Sindhabad is home to multiple communities, such as Baagri and Jogi, which were displaced in 2010’s Super flood. More than 150,000 people are still living there in vulnerable conditions (Mapping Displacement, 2023a).

Similarly, more than 500 families are living in temporary tents provided by the government and non-government organizations after the Super Flood of 2010 for the affected people of Shahdadkot, Qambar, Dadu, and Jacobababd Sindh at 500 Quarter, Musharraf Colony. However, after almost 1 and a half decades, no recovery or rehabilitation plan has been implemented for the affected (Mapping Displacement, 2023b). With time, the people living in these communities have established a sense of harmony and stability. Not only this, but people displaced due to religious conflicts are still looking towards authorities for resettlement. For instance, people living in Rimsha Colony in Islamabad’s H-9/2 slum area are originally from Mehrabadi, G-12. These people are displaced due to the blasphemy case of the 12-year-old Christian girl, Rimsha Masih, who was falsely accused of hurting the Muslims’ sentiments in 2012. The whole community had to face the consequences of that accusation, and eventually, all the Christian families shifted to the temporary shelter in the Rimsha Colony (Mapping Displacement, 2023c). Besides, [minority] people living in Lyari’s Slaughterhouse have also faced displacement in 2013 due to various challenges and threats from the violent neighbourhoods, i.e., Lyari gangs. The fear of losing their lives, properties, and especially rape threats for their daughters, incited them to take refuge in other areas of Karachi. While people who weren’t able to afford to live in other areas were forced to come back, nearly 59% are still displaced, waiting for the government to take any step regarding replacement and relocation, which is impacting them financially and imposing barriers in the education of their children (Mapping Displacement, 2023d). Nevertheless, the government seems futile in carrying out resettlement operations for the displaced.

Planning Commission

The southeastern part of the Sindh province has been considered the “calamity hit” area during the 2022 flood since it broke its thirty-year average and received 400% more rain, six times more than its average yearly rainfall. Around 4.4 million acres of agricultural land were devastated, and casualties rose to 799 (Rafique et al., 2023). The rain caused heavy flooding that affected 50 million residents of Sindh, and around 2.7 million houses were partially and fully damaged even before the flooding and heavy rains of 2022. Also, a linear trend at a rate of 1.6% was observed in partial and improperly built structures in Sindh from 1998 to 2017. Sindh government took notice and devised an initiative, namely “Sindh People’s Housing for Flood Affectees” (SPHF), with a budget of $1.5 bn. The World Bank has also supported the programme with 500 million USD, besides providing technical support for building the partially and completely destroyed houses in Sindh due to the flood of 2022 (SPHF, 2023). The work in this regard is still ongoing, but the response rate is very slow. Out of 2.7 million houses, nearly 300 houses have been handed over to the owners. Authorities ensure that they provide ownership of the houses to the females of the household in order to encourage women’s empowerment. It’ll be a success story on behalf of GoS, but since it is still in process, it will be interesting to see if the project finishes successfully and what impact it’ll create on a massive level.

Additionally, in response to the 2022 floods, the Planning Commission, which functions under the auspices of the Federal Ministry of Planning, Development, and Special Initiatives, developed the Resilient Recovery, Rehabilitation, and Reconstruction Framework (4RF). This framework is Pakistan’s strategic policy and prioritisation document to guide the recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction of the country post-2022 floods. And while the framework, which remains heavily focused on the rehabilitation of habitat, also has people-centred socio-economic recovery among its aims. Nevertheless, with the SPHF and framework still in place, there’s a lack of information at this point since the SPHF project is in progress, and it’ll be too early to assume and say anything. Also, for the framework, very little has been shared recently in terms of how much of that recovery has materialised when it comes to helping effectively resettle communities that were displaced as a result of the 2022 floods.

Ministry of Climate Change

Pakistan’s climate change ministry, apart from working with various government departments, other ministries, international NGOs, and other partners on climate-related projects, has also established a dedicated Climate Finance Unit to coordinate with relevant stakeholders to avail global climate finance opportunities. This unit focuses on developing readiness programmes by tapping into global climate finance, thereby enhancing the capacity of stakeholders and promoting awareness for the implementation of Pakistan’s climate change policy.

This unit aims to ultimately improve climate readiness and governance in order to make Pakistan and Pakistanis adopt sustainable practices.

World Wildlife Fund

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) is among some of the international NGOs that look towards the issue of climate change and the catastrophes resulting from it.

In the aftermath of the 2022 floods, the WWF focused on the communities affected in Cheil Beshigram in Swat, providing them with 800 fruit and fast-growing tree species and 45 kg of fodder seeds and supporting 100 households in kitchen gardening and an additional 30 households by providing them with fuel-efficient stoves. The INGO also distributed honey bee boxes among community members to provide them with an alternative source of income.

More recently, WWF began working with the Ministry of Climate Change on a project titled Recharge Pakistan, which aims to reduce climate vulnerability and contribute to Pakistan’s climate adaptation efforts. This project, which managed to secure $77.8 million in funding, is focused on helping communities adopt “nature-based solutions to mitigate flooding.” The effort and emphasis of WWF towards climate change are remarkable and undeniable; however, it doesn’t extend its support to address the plight of the already displaced communities and their resettlement challenges, which is a noteworthy concern, especially after Flood 2022.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

While the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) primarily works with Afghan refugees and asylum seekers in Pakistan, it has in the past supported camps hosting Pakistanis internally displaced following security operations in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP).

UNHCR co-leads the international IDP Protection Expert Group with the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Internally Displaced Persons and the Global Protection Cluster (GPC) to offer coordinated and collaborative support (UNHCR, 2024a). However, its focus in Pakistan remains on Afghan refugees, and its work does not centre on Pakistanis displaced internally due to conflict or climate-related events (UNHCR, 2024b).

Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)

Also a part of the UN, the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) led the international community’s efforts to develop a robust humanitarian architecture in the aftermath of Pakistan’s catastrophic floods in 2022. However, when it comes to sustained efforts to assist long-term assistance and resettlement of communities to their original abodes, OCHA, UNHCR, and even local departments and authorities do not appear to have effectively led such an effort.

International Organisation for Migration

The United Nations’ International Organisation for Migration (IOM), which works with migration in Pakistan, also pledged to focus its humanitarian assistance on the country’s internally displaced communities as well as the cross-border displacement of Afghans. In Pakistan, the IOM implements humanitarian and development activities in coordination with the NDMA, the PDMAs, the Ministry of Climate Change, and other relevant departments.

Challenges and Considerations:

While the institutional framework involves multiple stakeholders, challenges persist in ensuring effective resettlement and rehabilitation. The allocation of funds, coordination among diverse entities, and the need for specialized legal frameworks to protect the rights of displaced individuals and communities are areas that require continuous attention.

A legal framework recognizing the unique challenges facing displaced communities is an essential step toward eventual recovery. These communities should be protected against bias on displacement status, ethnicity, and gender and should be ensured equitable treatment in policies and programmes. The framework should also ensure the protection of property rights with mechanisms for restitution or compensation in cases of loss and/or damage. The legal framework should also ensure the communities’ access to essential services, such as education, healthcare, water, and sanitation.

Additionally, developing a structural, legal, and stakeholder framework to work alongside institutional response for relief and rehabilitation will promote economic well-being through provisions for employment, vocational training, and livelihood support. Ultimately, the legal framework should align with international standards, including the Guiding Principles on Displacement. The implementation of such a broad and specialized framework will protect the rights of internally displaced Pakistanis, fostering a more just and equitable society post-trauma.

1. Need of an Hour: Define Displacement for Policy Reforms

Defining displacement within policy frameworks serves several critical purposes, including:

Clarity and Consistency: Providing clear terminology in social policy making is crucial for ensuring clarity, consistency, and effective communication among stakeholders. It helps create a shared understanding of key concepts, which is essential for developing, implementing, and evaluating policies. Terminology provides a structured framework for analyzing social issues and facilitates interdisciplinary collaboration, aiding in the comparison of research findings and the formulation of evidence-based policies. Clear terminology also raises public awareness and engagement, making information accessible and relatable, thereby encouraging public participation. Moreover, it aligns local policies with international standards, ensuring a cohesive approach to addressing global issues.

For example, defining terms like “refugee,” “migrant,” and “displaced person / community” precisely is essential in humanitarian policies to ensure that each group receives the appropriate legal protection and support. Similarly, in public health policy, clearly distinguishing between “pandemic,” “epidemic,” and “endemic” is crucial for implementing the right strategies to manage and contain diseases.

Legal and Protection Frameworks: Defining displacement within legal frameworks such as International Humanitarian Law, International Refugee Law, International Human Rights Law, International Disaster Response law, etc., establishes the rights and entitlements of displaced individuals (UNHCR & International Protection, n,d.; Relief Web, 2013). It helps in formulating laws and regulations such as NDRMF, The National Calamities Prevention and Relief Act, The National Disaster Management Act, etc. (IFRC, 2020, p.28), to safeguard their rights, access to aid and protection under national and international laws.

Targeted Interventions: A well-defined definition enables policymakers to target interventions and resources more effectively. It helps identify specific needs, vulnerabilities, and challenges faced by displaced populations, ensuring tailored and targeted support.

Data Collection and Reporting: Data collection is crucial for defining displacement in policy making in Pakistan, even when the data is weak. It provides essential evidence to understand the scale, nature, and impact of displacement within the country. Accurate and comprehensive data will allow policymakers to assess the number of affected individuals, identify trends and patterns, and tailor interventions to meet specific needs. This ensures efficient resource allocation and the ability to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of policies. Despite challenges in collecting robust data in Pakistan, even incomplete information can prompt necessary humanitarian responses and highlight urgent needs, such as healthcare and sanitation. Weak data can still provide valuable insights and be progressively improved through better methodologies and technology. Data collection and reporting will enable targeted and impactful interventions for displaced populations.

International Cooperation and Consensus: Within the international community, a standardized definition facilitates cooperation, collaboration, and consensus-building among countries and organizations. It enables unified efforts to address displacement issues on a global scale.

Preventative Measures: Understanding the various forms and causes of displacement helps in developing proactive strategies to prevent displacement where possible. This could involve disaster risk reduction, conflict resolution, or climate adaptation measures.

Defining displacement within policy reforms is foundational. It sets the stage for targeted, effective, and rights-based interventions to address the multifaceted challenges faced by displaced populations, ensuring their protection, well-being, and inclusion within societies.

2. NADRA for Empowering Displaced Communities

The National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) in Pakistan holds a vast repository of citizen data, which can be harnessed to assist in displacement scenarios in several ways to facilitate locally displaced communities. This can easily curtail the data discrepancy, including under-reported or overly exaggerated numbers of the affected community.

Despite NADRA’s success in using its database for verifying displaced families and facilitating financial aid through programs like the Livelihood Support Grant and Child Wellness Grant in 2014’s Operation Zarb-e-Azb, it has not extended similar efforts for other climate and conflict-related displacement. NADRA’s extensive database, which proved effective in tribal areas impacted by militancy, could significantly aid in identifying the extent of climate and conflict displacement and in providing relief and rehabilitation to affected communities. Utilizing biometric verification and secure disbursement mechanisms, NADRA could ensure efficient and transparent assistance to those displaced by climate disasters, thereby improving their recovery and return to normalcy. NADRA can help maintain transparency, among several other things mentioned below:

Identification and Registration: NADRA data can facilitate the identification and registration of displaced individuals. By cross-referencing existing databases, including local governance bodies, District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA), Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA), and Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), the authorities can track and locate displaced persons, ensuring they receive necessary aid and support.

Verification of Displaced Individuals: NADRA data provides a reliable means to verify the identities of displaced individuals. This verification process ensures that aid and support reach the intended recipients, minimizing fraud or misallocation of resources.

Family Reunification: In cases of family separation during displacement, NADRA data can aid in reuniting families by verifying familial relationships through documented records.

Assistance in Aid Distribution: Leveraging NADRA data can streamline aid distribution processes. It helps in ensuring that relief efforts and resources are directed to legitimate beneficiaries in an organized and efficient manner.

Monitoring and Tracking Displacement: Over time, NADRA data can help track the movement and patterns of displacement. This information aids in developing proactive strategies for disaster response, relocation, and long-term rehabilitation plans.

Policy Formulation and Planning: Analyzing NADRA data on displaced populations allows policymakers to understand the demographic makeup, needs, and locations of these communities. This information is crucial in formulating targeted policies and plans for their resettlement and support.

Security and Protection: NADRA data can enhance security measures by providing authorities with accurate information about the displaced population, helping in preventing identity-related crimes or security threats within these communities.

However, while utilizing NADRA data to assist in displacement scenarios offers numerous advantages, it’s crucial to ensure ethical and legal considerations, such as privacy, data protection, and consent, are strictly adhered to during its usage. Collaboration between relevant authorities, data protection experts, and humanitarian organizations is essential to responsibly harness NADRA data to assist displaced populations.

3. Establishing an Independent Monitoring Cell on Displacement

As part of the policy recommendation on displacement, there is a proposal to institute a dedicated monitoring cell specifically focused on climate and conflict-induced displacements in Pakistan. This monitoring cell will operate as an online portal, facilitating real-time updates on displacement data. It aims to maintain a comprehensive record of ongoing displacements, mapping these occurrences while archiving historical data for accountability purposes. Collaborative efforts will ensure that this monitoring cell provides open-source data to support rehabilitation initiatives for affected communities.

The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) is responsible for climate-related monitoring and has developed a mobile application for Android phones that offers real-time updates and early warning systems. However, several gaps exist in these efforts. The NDMA’s approach is largely proactive and anticipatory, aimed at reducing disaster risk through systemic efforts, but it focuses solely on climate-related displacement and does not cover conflict-induced displacement. Additionally, the NDMA’s digital portal often overlooks unprecedented events, including sudden displacement. Furthermore, with only 31% of the population in Pakistan owning smartphones (Howarth, 2023), the NDMA’s early warning system reaches a limited audience.

To address these gaps, the proposed monitoring cell will complement NDMA’s efforts by including conflict-induced displacement in its scope. It will offer a more inclusive approach by providing data accessible to a broader population, ensuring comprehensive coverage of all types of displacement.

This dedicated monitoring cell on climate and conflict displacement can effectively overcome caveats and challenges while serving as a crucial policy measure for the following reasons:

Timely Response to Emerging Challenges: The cell enables the promptly identification of emerging challenges related to displacement. This allows for timely response and adaptation of policies and interventions to address evolving needs and vulnerabilities.

Comprehensive Data Analysis: Continuous monitoring facilitates comprehensive data analysis, helping to understand the complexities and nuances of climate and conflict-induced displacement. This depth of analysis aids in formulating nuanced policies tailored to specific situations.

Evidence-Based Decision-Making: By providing reliable data and analysis, the monitoring cell supports evidence-based decision-making. This minimizes the guesswork and ensures that policies and interventions are grounded in factual information, leading to more effective outcomes.

Improved Coordination and Collaboration: The cell acts as a hub for collating and disseminating information to various stakeholders. This fosters coordination among different agencies, organizations, and governmental bodies involved in addressing displacement, leading to more efficient and cohesive efforts.

Monitoring Progress and Impact: It enables the ongoing monitoring of the effectiveness and impact of policies and interventions implemented to address displacement. This allows for adjustments and improvements, ensuring that efforts are yielding desired outcomes and serving affected populations adequately.

Risk Assessment and Planning: The cell conducts continuous risk assessments, aiding in proactive planning and risk reduction strategies. This proactive approach helps in mitigating potential displacement risks and building resilience within communities.

Enhanced Advocacy and Awareness: Reliable data and reports generated by the monitoring cell serve as valuable resources for advocacy efforts. They raise awareness about displacement issues, advocating for support and resources from stakeholders at various levels, including international agencies.

Adopting a dedicated monitoring cell as a policy measure is crucial as it offers a systematic, proactive, and informed approach to addressing the complexities of climate and conflict displacement. It not only helps in overcoming challenges but also ensures a more efficient, coordinated, and responsive approach towards assisting and protecting affected populations.

4. Integrate NCHR into the Response Framework for Climate and Conflict Displacement:

Engaging the National Commission of Human Rights (NCHR) in addressing climate and conflict displacement can be highly beneficial due to its mandate to protect and promote human rights. Integrating NCHR into the response framework for displacement enhances accountability, ensures the protection of rights, and fosters a more robust response to these crises.

Formalize Collaboration: I recommend formal collaboration and partnerships between relevant government agencies, including IOM and non-governmental organizations and CSOs responsible for displacement issues and the NCHR. This includes integrating NCHR representatives into displacement response planning committees or task forces.

Advocacy and Policy Guidance: Encourage the NCHR to advocate for policies and legal frameworks that safeguard the rights of displaced populations. This could involve conducting research, issuing recommendations, and advocating for the implementation of human rights-based approaches in displacement responses.

Monitoring and Reporting: Empower the NCHR to monitor and report on human rights violations and gaps in services for displaced populations. This could involve regular assessments, fact-finding missions, and reporting on the conditions of displaced communities.

5. Habilitation before Rehabilitation

To overcome food insecurity, thinking of habilitation before rehabilitation is an important policy measure for climate and conflict displacement. It helps build resilient societies and avoids secondary displacement. To approach stakeholders like the Planning Commission of Pakistan, as well as NDMA, it is imperative to have a full understanding of what it means when we are saying Habilitation before Rehabilitation:

Immediate Needs and Vulnerabilities: Habilitation focuses on the immediate needs and vulnerabilities of displaced populations. Addressing urgent requirements such as shelter, food, water, and healthcare ensures the basic survival and well-being of affected communities.

Protection and Safety: Prioritizing habilitation measures, including emergency shelter and essential services, safeguards the safety and security of displaced individuals and communities. It mitigates risks associated with exposure to harsh environmental conditions or conflict-affected areas.

Prevention of Secondary Displacement: Addressing immediate needs helps prevent secondary displacement. By providing essential support early on, the likelihood of displaced populations being forced to move again due to unmet needs decreases.

Human Dignity and Rights: Habilitation measures uphold the dignity and rights of displaced individuals by immediately addressing their most pressing needs. It ensures that fundamental rights to shelter, food, healthcare, and safety are respected and met.

Community Resilience and Coping Mechanisms: Early habilitation interventions contribute to building community resilience and coping mechanisms. Strengthening these aspects empowers communities to better withstand and recover from displacement challenges.

Laying the Foundation for Rehabilitation: Effective habilitation sets the groundwork for successful rehabilitation efforts. Once immediate needs are met, communities are better positioned to engage in and benefit from long-term rehabilitation and recovery initiatives.

Humanitarian Imperative: There is a humanitarian imperative to act swiftly in response to immediate needs. Prioritizing habilitation acknowledges the urgency of the situation and demonstrates a commitment to addressing the pressing challenges faced by displaced populations.

To be precise, focusing on habilitation before rehabilitation acknowledges the criticality of addressing immediate needs, protecting vulnerable populations, and laying the groundwork for long-term recovery. It ensures a more effective and holistic approach to addressing the multifaceted challenges of climate and conflict displacement.

6. Local Government as a Crucial Partner to Give Visibility to Invisible Climate and Conflict Displacements

Recognizing the pivotal role of local governments in addressing the challenges of climate and conflict displacement, it is imperative to establish strategic partnerships that leverage their capacities, resources, and proximity to affected communities. Local governments serve as critical stakeholders in providing immediate assistance, facilitating long-term recovery, and fostering community resilience. To optimize their involvement and efficacy in addressing displacement, the following policy recommendations are proposed:

Empowerment through Capacity Building: Implement capacity-building programs tailored for local governments, enhancing their knowledge, skills, and resources to effectively respond to and manage displacement situations. This includes training PDMA and DDMA staff as well as local government department officers, including commissioners, assistant commissioners, mukhtiarkaars, agriculture and wildlife department staff, etc. on disaster response, conflict resolution, and community engagement strategies.

Facilitate Coordination and Collaboration: Foster partnerships between local governments, national authorities, civil society organizations, and international stakeholders. Facilitate platforms for dialogue and collaboration to synchronize efforts, share resources, and ensure a cohesive and comprehensive approach to displacement management.

Enhance Local-Level Data Collection: Encourage and support local governments in collecting accurate and timely data on displacement within their jurisdictions. Enable the establishment of robust information systems to track displacement trends, demographics, and needs, facilitating evidence-based decision-making.

Inclusive Policy Development: Engage local governments in the formulation and implementation of policies and programs addressing displacement. Ensure their active participation in decision-making processes to foster inclusive, community-driven solutions that consider local contexts and priorities.

Resource Allocation and Support: Allocate adequate financial resources and provide technical support to local governments for the implementation of displacement-related initiatives. This includes funding for infrastructure development, service provision, and capacity enhancement.

Promote Community Engagement and Integration: Encourage local governments to foster community participation and inclusion of displaced populations in local decision-making processes. Support initiatives that promote social cohesion, integration, and access to services for both displaced and host communities.

Advocate for Legal Frameworks and Support Services: Collaborate with local governments to advocate for legal frameworks that protect the rights of displaced populations and provide access to essential services, including healthcare, education, and livelihood opportunities.

Fostering strong partnerships with local governments is imperative in addressing the multifaceted challenges of climate and conflict displacement. Embracing these recommendations will harness the local-level knowledge, resources, and proximity to affected communities, ensuring a more effective, inclusive, and sustainable response to displacement.

In short, it is a clear expectation that robust and transparent practices support decision-making and that the long-term adverse consequences of climate and conflict displacement for future generations are incorporated into local governments’ planning, decisions, and actions.

Most displaced communities in immediate need are situated outside formal camps, whether in informal locations, host communities, or in rural and urban areas. Likewise, the displaced individuals and communities still residing in relief camps overseen by the government encounter obstacles to returning and continue to require assistance. The magnitude of the challenge that displacement poses thus requires a comprehensive and coordinated effort from governmental and non-governmental entities, as well as international partners. The existing institutional framework has made strides in disaster response and relief, but the focus must shift toward sustained efforts for rehabilitation and resettlement to ensure the long-term well-being of affected communities. Continuous evaluation and adaptation of strategies will be essential to meet the evolving challenges posed by internal displacement in Pakistan.

- Alkhateeb, G. (2023). Post-conflict landscape: Patterns of change in physical, social, and cultural landscapes in the wake of urban displacement. ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES. https://dspace.emu.ee/bitstream/handle/10492/8177/Ghieth_Alkhateeb_2023MSc_LA_fulltext.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

- Howarth, J. (2023, January 26). How Many People Own Smartphones? 80+ Smartphone Stats. Exploding Topics. https://explodingtopics.com/blog/smartphone-stats

- Human Rights Watch. (2023). Pakistan: Drop Threat to Deport Afghans. https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/10/12/pakistan-drop-threat-deport-afghans

- Hunter, M. (2024). The Unjust Removal of Afghans from Pakistan. https://cscr.pk/explore/themes/politics-governance/the-unjust-removal-of-afghans-from-pakistan/

- IFRC. (2020). International Disaster Response Law (IDRL) in Pakistan. https://disasterlaw.ifrc.org/sites/default/files/media/disaster_law/2020-09/Pakistan%20IDRL%20Report%20FINAL.pdf

- Interactive Country Fiches. (2023). Pakistan. https://dicf.unepgrid.ch/pakistan/climate-change

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Center. (2022). Pakistan. https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/pakistan#:~:text=Around%2070%20per%20cent%20of,out%20of%20reach%20of%20assistance.

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Center. (2023). GUIDING PRINCIPLES ON INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT. https://www.internal-displacement.org/internal-displacement/guiding-principles-on-internal-displacement#:~:text=The%20Guiding%20Principles%20are%2030,the%20achievement%20of%20durable%20solutions.

- International Committee of the Red Cross. (2020). Understanding Urban Resilience: MIGRATION, DISPLACEMENT & VIOLENCE IN KARACHI. International Committee of the Red Cross. http://karachiurbanlab.com/assets/downloads/Understanding_Urban_Resilience_Migration_Displacement_&_Violence_in_Karachi.pdf

- IOM UN Migration. (2023). Pakistan Crisis Response Plan 2023 – 2025. https://crisisresponse.iom.int/response/pakistan-crisis-response-plan-2023-2025

- IPC ACUTE FOOD INSECURITY ANALYSIS. (2023). Pakistan. https://fscluster.org/sites/default/files/documents/ipc_pakistan_acute_food_insecurity_april_2023_january_2024_report.pdf

- Islamic Relief Web. (2023). Climate Crisis in Pakistan: Voices from the Ground. https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/climate-crisis-pakistan-voices-ground#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Global%20Climate,the%20years%201999%20to%202018.

- Khan, M. S., & Sepulveda, L. (2022). Conflict, displacement, and economic revival: the case of the internally displaced minority entrepreneurs in Pakistan. Strategic Change, 31(4), 461-477. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2515

- Mapping Displacement. (2022). From Climate Crisis to Political Gambit: Exploring the Displacement-Peace Connection in Pakistan. https://thedisplacement.com/research-analysis/from-climate-crisis-to-political-gambit-exploring-the-displacement-peace-connection-in-pakistan/

- Mapping Displacement. (2023a). Karachi – Sindhabaad settlement. https://thedisplacement.com/displacement-stories/sindhabaad-settlement-profile/

- Mapping Displacement. (2023b). Karachi – 500 Quarters, Musharraf Colony, Hawkesbay. https://thedisplacement.com/displacement-stories/500-quarters-musharraf-colony-hawkesbay/

- Mapping Displacement. (2023c). Islamabad – Rimsha Colony, H-9/2. https://thedisplacement.com/displacement-stories/rimsha-colony-sector-h9-2/

- Mapping Displacement. (2023d). Karachi – Slaughterhouse, Lyari. https://thedisplacement.com/displacement-stories/slaughterhouse-lyari/

- Othering and Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley. (2022). Climate Crisis, Displacement, and the Right to Stay. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/climatedisplacement/case-studies/pakistan

- Oxford Learners Dictionary. (2023). Displacement. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/displacement

- Rafique, N., Tehsin, A., & Yamin, F. (2023). Rising from the Waters: Sindh Navigates Recovery after the 2022 Floods. The World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2023/06/28/rising-from-the-waters-sindh-navigates-recovery-after-the-2022-floods

- Relief Web. (2013). International Legal Frameworks for Humanitarian Action: Topic Guide. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/international-legal-frameworks-humanitarian-action-topic-guide

- Sepka, M. (2017). Cross-border Displacement: Prevent, Prepare or Adapt to? https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=8928021&fileOId=8928022

- Shamsuddoha, M., Khan, S. M., Raihan, S., & Hossain, T. (2011). DISPLACEMENT CAUSES AND MIGRATION THE AND FROM CLIMATE HOT SPOTS CONSEQUENCES. Center for Participatory Research and Development. https://unfccc.int/files/adaptation/groups_committees/loss_and_damage_executive_committee/application/pdf/displacement_and_migration_from_the_hot_spots_in_bangladesh_causes_and_consequences.pdf

- SPHF. (2023). Who we are. https://www.sphf.gos.pk/who-we-are/

- Terminski, B. (2014). Development-induced displacement and resettlement: Causes, consequences, and socio-legal context. Columbia University Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271964071_Bogumil_Terminski_Development-Induced_Displacement_and_Resettlement_Causes_Consequences_and_Socio-Legal_Context_Ibidem_Press_Stuttgart_2015_580_p_Book_Presentation

- The Displacement. (2022). From Climate Crisis to Political Gambit: Exploring the Displacement-Peace Connection in Pakistan. https://thedisplacement.com/research-analysis/from-climate-crisis-to-political-gambit-exploring-the-displacement-peace-connection-in-pakistan/

- The Displacement. (2022a). Islamabad – Patterns of Climate-induced Displacement in Pakistan’s North. https://thedisplacement.com/displacement-stories/patterns-of-climate-induced-displacement-in-the-north-of-pakistan/

- The Displacement. (2022b). Karachi – Sindhabaad settlement. https://thedisplacement.com/displacement-stories/sindhabaad-settlement-profile/

- The Displacement. (2022c). Islamabad – Jaaba Taili, Burma Town. https://thedisplacement.com/displacement-stories/jaaba-taili-burma-town-ward-18-islamabad/

- UNHCR & International Protection. (n.d.). Chapter 3: The Legal Framework. https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/legacy-pdf/44b500902.pdf

- UNHCR. (2024a). Korea and UNHCR mark contribution of 1 million dollars to support refugees, local communities in Pakistan. https://www.unhcr.org/pk/

- UNHCR. (2024b). Pakistan. https://www.unhcr.org/countries/pakistan

- United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change. (2021). Pakistan NDC 2021. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-06/Pakistan%20Updated%20NDC%202021.pdf

- United Nations High Commission for Refugees. (2011). THE 1951 CONVENTION AND ITS 1967 PROTOCOL. https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/legacy-pdf/4ec262df9.pdf

- Weinbaum, M. G. (2023). Afghan refugees as victims of Pakistan and Afghanistan’s clashing security interests. https://www.mei.edu/publications/afghan-refugees-victims-pakistan-and-afghanistans-clashing-security-interests